|

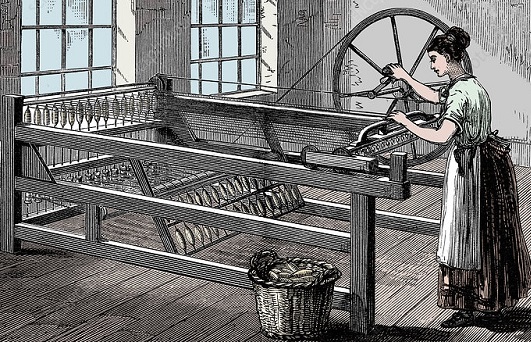

1 Spinning by

Hand

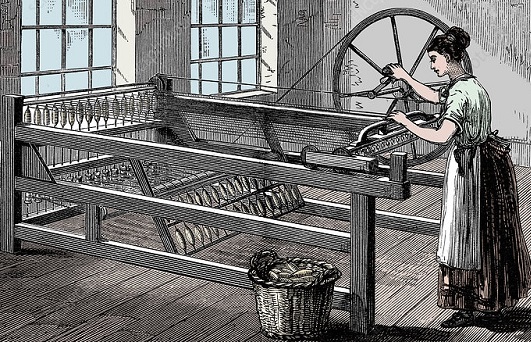

The 'spinster'

in the foreground holds the roving (a thick band of combed wool) in her left hand. The roving is attached to the spindle. She pulls it out to make the yarn (thread) thinner. At the same time, she turns the large 'muckle wheel', which turns the spindle, which twists the yarn.

It took two or three spinners to supply yarn for one weaver The yarn was thick and weak.

|

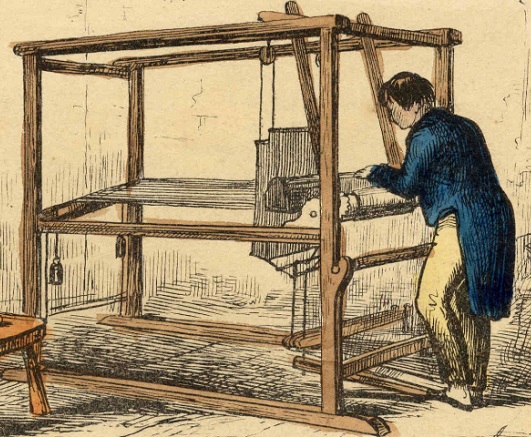

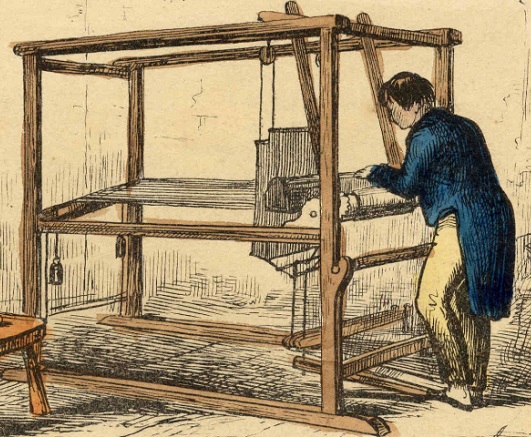

2 A Hand-Loom Weaver

A foot pedal raises every other warp thread to create the 'shed' (gap). In his left hand he holds the shuttle, which carries the weft thread. He passes the shuttle through the shed

from one hand to the other. The maximum width of cloth is 70 centimetres (a 'shortcloth’),

limited by how far he can reach. To make wider cloth needed two weavers, to throw the shuttle back and forth.

|

|

|

3 Kay's Flying

Shuttle

|

In the eighteenth century, cloth was made by hand in the workers' own homes (see pictures 1-2

above). This was known as the 'Domestic System'. It was by

no means as inefficient and wasteful as some textbooks would have you

believe ... but it was limited by human skill and muscle-power, and

production grew only gradually.

Then, however, in 1733, John Kay of Bury invented a weaving

machine called the flying shuttle. He put the shuttle on wheels,

so weavers could knock it backwards and forwards with a simple mechanism

called a picker. This allowed wider cloth to be made, more quickly. |

|

4 Hargreaves's

Spinning Jenny

The wheel has been adapted so that it turns 16 spindles.

A clamp is placed on a moving carriage which allows the spinner to pull out all the threads at once.

|

The spinners could not keep up – there was a need for an invention which would speed up spinning.

In fact, three machines were invented:

In about 1764, James Hargreaves of Blackburn invented the 'spinning Jenny' (sec picture

4).

This allowed the spinner to spin many threads at the same time, although

the machine was still worked by muscle-power, and the yarn was not as strong as that produced by hand spinners. |

|

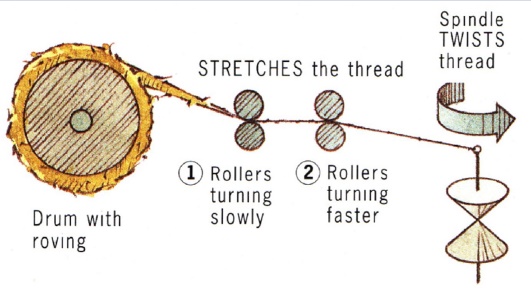

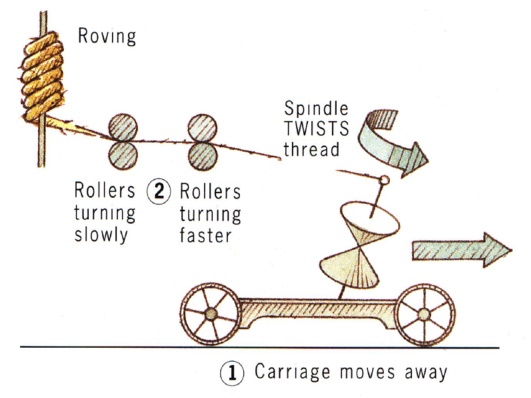

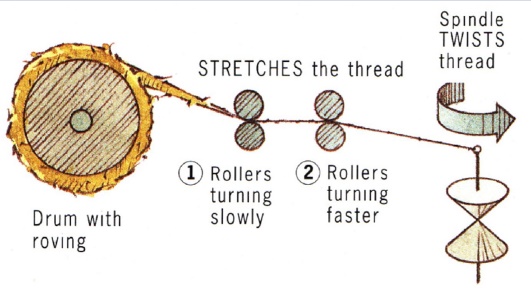

5 Arkwright's

Water Frame

Rollers 1 turn more slowly than rollers

2, which stretches the roving in between. A spindle twists the yarn.

|

Soon after, a better spinning machine was invented in about 1769 by Richard Arkwright of Preston (although some people say he stole the idea from his partner)

– Arkwright's machine produced a strong, thick thread (see diagram 5).

This large machine needed a water wheel to power it, and became known as the 'water frame'.

Consequently, in 1771 Arkwright built Cromford Mill, the world's first successful water powered cotton spinning factory ... and 'the Factory Age' began. |

|

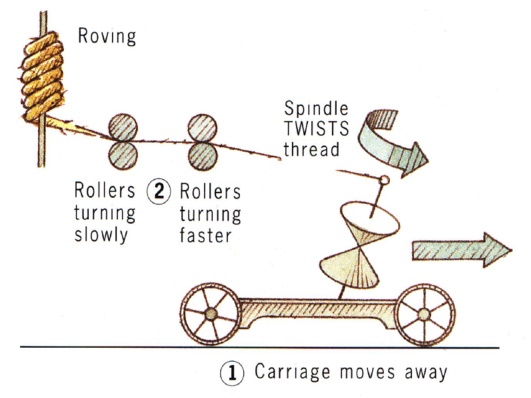

6 Crompton's

Mule

To stretch the roving, Crompton used both Hargreaves' idea of a moving carriage

(1) and Arkwright's idea of rollers (2). His machine was therefore nicknamed the 'mule' (a mule is a cross between a horse and a donkey).

|

In 1779, Samuel Crompton of Bolton invented a machine which spun thread that was finer and stronger than anything

before (see diagram 5).

More and more employers bought the new machines. Spinning became mechanised

– by 1812 one spinner operating a machine in a factory could make as much as 200 domestic spinsters could have made 50 years earlier. |

|

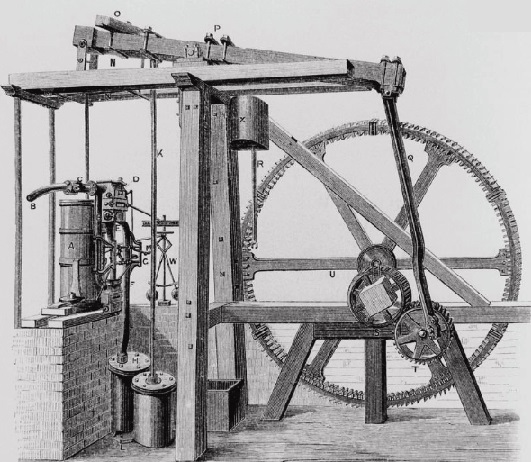

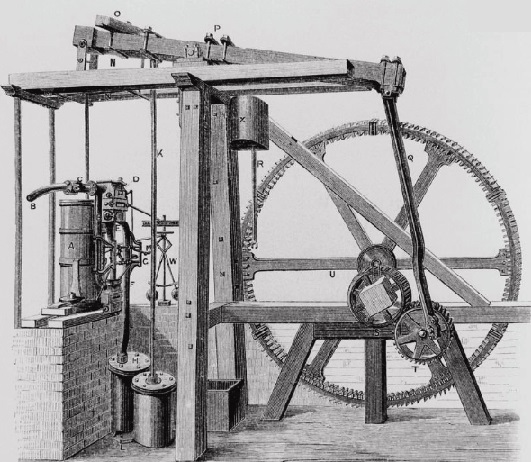

6 Watt's Steam

Engine

|

The introduction of machinery was helped by the development of the steam engine.

-

In

1712, Thomas Newcomen had invented a simple steam engine, which had been used to drain the coal mines.

-

In 1765 James Watt improved Newcomen's design, and in 1781 he invented the 'sun and planet gear', an invention which turned the up-and-down motion of the steam engine into rotary (round and round) motion.

This meant that steam engines could now be attached to drive belts and

used to power machinery in factories. Production of yarn increased

greatly; so much so that the hand-loom weavers could not weave all the thread being made by the spinning machines.

There was clearly a need for a weaving invention

– which happened when a vicar from Leicestershire, Edmund Cartwright, invented a power-loom

(1785). By 1800 the design had been improved and businessmen

began to use these looms in their factories; by 1850 weaving, too, was

fully mechanised. |

|